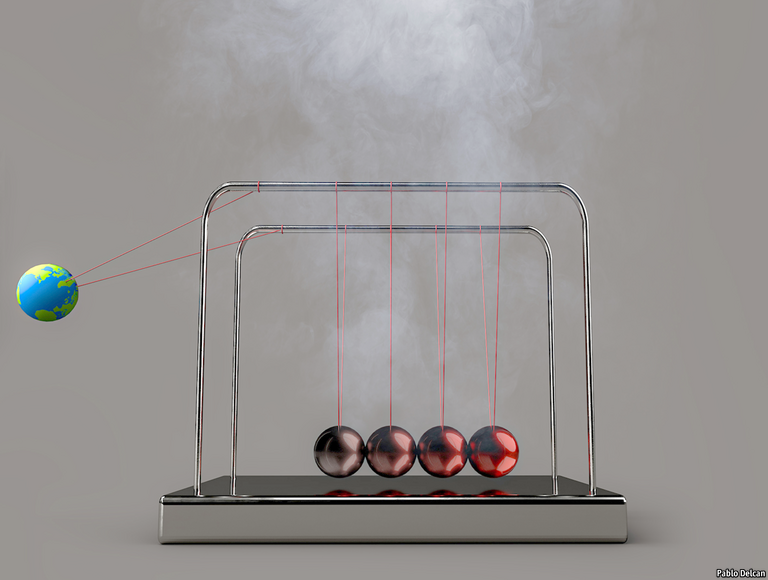

地球温暖化に対する世界的な取り組みは、1988年のトロント会議から、リオ、京都、コペンハーゲン、2015年のパリ協定まで随分と時間がかかりましたが、ようやく世界が同じフレイムワークで、温室効果ガスの削減目標値に取り組んでいるように見えます。この記事の中では再生可能エネルギーのコストが下がっていることが追い風になっていると書かれていますが、日本こそ、この分野に選択と集中をして、日本のお家芸としてお手本になれないでしょうか。

日本語訳参考例

1988年6月、科学者、環境活動家、政治家が「変化する環境に関する世界会議」のためにトロントに集まりました。彼らを最も驚かせたその変化の側面は、温室効果ガスである二酸化炭素の蓄積でした。 1950年代後半、大気中の二酸化炭素レベルの体系的な観察が始まったとき、その濃度は約31ppm (parts per millionの略で100万分の1の意味)でした。その年の夏までに、それは350ppmに達しました、そしてその年の熱波は北アメリカの大部分に記録的な猛暑をもたらしていました。トロント会議では、世界の二酸化炭素排出量を2005年までに20%削減する国際的な取り組みを求めています。

リオデジャネイロでの「地球サミット」で、国連のメンバーは、気候変動に対する危険な人為的干渉を防ぐレベルでの「温室効果ガス濃度の安定化」を約束する気候変動に関する枠組み条約(UNFCCC = Unated Nation Framework Convention on Climate Change)に合意しました。

この安定化という言葉は排出量の相応量の削減を期待させましが、実際この条約では、トロントで合意した2005年までに20%削減に沿った目標を設定をすることはありませんでした。

特定の排出削減目標は、リオの5年後に京都で合意されました。それらはグローバルな範囲ではなく、二酸化炭素の主な放出国である先進国にのみ課せられました。また、その先進国も積極的でありませんでした。そして、京都議定書は、当時世界最大の放出国であったアメリカでは批准されることはありませんでした。

排出削減への抵抗のもう一つの原因は中国の台頭でした。そのGDPは、リオのサミット以降20年間で7倍に増加しました。その二酸化炭素排出量は、27億から96億トンへと、3倍以上に増加しています。中国はこの世界を変えてしまう副作用を抑制することに真の関心を示しませんでした。そしてその当時は発展途上国であったので、京都議定書によってそうすることは概念的に義務付けられることすらされなかったのです。- 京都プロトコルが発令されてから10年余りで中国はアメリカよりも多く放出する国となっていますが。この事実に対する憤慨は、一部の先進国が中国の責任にますます不満を抱くようになった理由の1つでした。 2009年のコペンハーゲン首脳会談では、中国のやる気のなさにより、京都を越えようとする試みをほぼ崩壊させてしまいました。

コペンハーゲンから6年後、国連のプロセスはリオ以来の最大の前進を果たすことになりました。それがパリ協定です。これでようやく、具体的にグローバルでのターゲットが設定されました。大気中の温室効果ガスのレベルは、産業革命以前のレベルを超えて平均気温が2°Cをはるかに下回るレベルで、今世紀の後半までに安定化され、1.5°Cに保つために多大な努力が払われました。署名されたすべての先進国と開発途上国は、その目的に向けて国内行動に取り組むことが求められました。成功の理由はいくつかありました。アメリカと中国の間の事前協議。巧みなフランス外交。開発途上国による用心深い交渉。しかし、おそらく最も重要なのは、再生可能エネルギーのコストが急落し、フィールドへの投資が急増したことでした。高エネルギーのライフスタイルを継続しながら排出量を削減することは、新たに可能性を感じました。

単語

carbon dioxide = 二酸化炭素

greenhouse gas = 温室効果ガス

anthropogenic = 人為的起源の、人類発生の

ratify = 批准する、承認する

curb = (強く)抑制する

resentment = (長く続くまたはうっせきした)憤り、立腹

strenuous = 奮闘的な、熱心な、奮闘を要する

canny = 先の読める、利口な、慎重な、用心深い、(金銭的に)抜けめのない、倹約な、よい、すばらしいtumbling = (価格)が急落する

英文

In June1988 scientists, environmental activists and politicians gathered in Toronto for a “World Conference on the Changing Atmosphere”. The aspect of its changing that alarmed them most was the build-up of carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas. In the late 1950s, when systematic monitoring of the atmosphere’s carbon-dioxide level began, it stood at around 315 parts per million (ppm). By that summer, it had reached 350ppm—and a heatwave was bringing record temperatures to much of North America. The Toronto conference calling for an international effort to reduce global carbon-dioxide emissions by 20% by 2005.

At an “Earth Summit” in Rio de Janeiro, the UN’s members agreed on a framework convention on climate change (UNFCCC) which committed them to the “stabilisation of greenhouse-gas concentrations…at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system”.

Despite the fact that such stabilisation implied impressive cuts in emissions, the treaty set no targets along the lines of Toronto’s 20% by 2005.

Specific emission cuts were agreed upon five years after Rio, in Kyoto. They were not global in extent, applying only to developed countries, which were responsible for most of the emissions. They were not ambitious either. And the Kyoto protocol was never ratified by America, then the largest global emitter.

Another source of resistance to emissions reduction was the rise of China. Its GDP, increased sevenfold in the 20 years after Rio. Its carbon-dioxide emissions more than tripled, from 2.7bn to 9.6bn tonnes. China showed no real interest in curbing this world-changing sideeffect, and because it was a developing country it was not even notionally obliged to do so by the Kyoto protocol—despite the fact that, before that protocol was ten years old, China was a bigger emitter than America. Resentment over this was one of the reasons some developed countries became increasingly unhappy with their commitments. China’s unwillingness to offer real action contributed to the near collapse of attempts to move beyond Kyoto at the Copenhagen summit of 2009.

Six years after Copenhagen, though, the UN process made its biggest step forward since Rio: the Paris agreement. This, at last, set a specific global target. Atmospheric greenhouse-gas levels were to be stabilised by the second half of this century at a level that would see an increase of the average global temperature over its preindustrial level well below 2°C, with strenuous efforts made to keep it down to 1.5°C. All the countries, developed and developing, that signed were required to commit to domestic actions towards that aim.There were several reasons for the success: prior talks between America and China; skilful French diplomacy; canny negotiation by developing countries. Perhaps the most important one, though, was that the cost of renewable energy was tumbling and investments in the field booming. Reducing emissions while continuing high-energy lifestyles felt newly possible.

コメントを残す