2025年には、団塊の世代の方が後期高齢者となる75歳を迎え、総人口1億2257万人のうち、後期高齢者の人口が2,180万人に達します。

団塊世代は、第一次ベビーブームが起きた昭和22年から24年に生まれた方を指し、出生数で約806万人、戦後の日本の高度経済成長を支えてきました。

ちなみに2021年度の出生数は81万1604人だったのでスケールが全然違いますね。

日本がバブル期にあたる1986年から19991年には、団塊世代は30代から40代を迎えまさに働き盛りで、生産者としても、消費者としても日本の経済を牽引してきたと言ってもいいのではないでしょうか。

そして、今団塊の世代は支える側から支えられる側に周り、雇用や医療、福祉といった分野へ大きな影響を及ぼすことから、2025年問題と言われています。

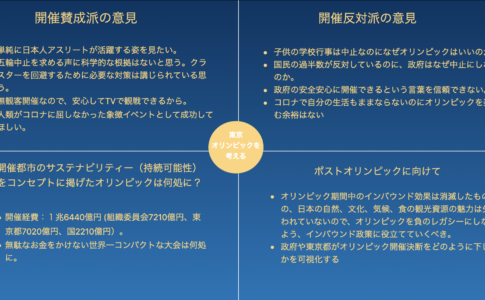

2025年問題はさておき、日本を取り巻く環境は厳しくなっていることはあるものの、メディアやSNSなどでは必要以上に悲観論や、日本は終わっているという論調が広がっていることにとても違和感を感じています。

日本悲観論の多くは、過去の日本の経済成長と比べて語られることが多くありますが、この数十年で、人口減、高齢化などにより経済のスケールが大きく縮小しているので、そもそも経済成長というスケールを求めていくこと自体に限界があると感じます。

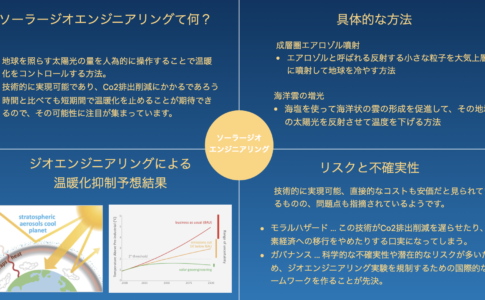

一方で、持続維持可能社会や、SGDs (持続可能な開発目標)、脱経済成長へのシフトなどのムーブメントも拡がりを見せています。

私自身は、日本は天然資源も乏しく、食料自給率も低く、また人的資源も先細りしていくなか、日本が生き残っていく道は、脱経済成長へのシフトが鍵だと信じています。

現内閣が目指す、新しい資本主義を完全に否定するわけではありませんが、その骨子が、成長と分配という相変わらずのモデルであることには危機感を感じられずにはいられません。

北欧などでは、循環型経済を試みるオランダや、人的資本への投資を進めるスウェーデンなど日本の参考になる施策もあるかもしれないので、私自身もっとこの分野の勉強をしていきたいと思います。

(English)

In 2025, the baby-boom generation will reach the age of 75, when they will be elderly in the latter half of their lives, and out of a total population of 122.57 million, the population of the elderly in the latter half of their lives will reach 21.8 million.

The baby-boom generation refers to those born between 1947 and 1949, when the first baby boom took place, and numbering approximately 8.06 million births, they have supported Japan’s rapid economic growth in the postwar period.

Incidentally, the number of births in FY2021 was 811,604, so the scale is totally different.

From 1986 to 1999, when Japan was in the midst of its bubble period, the baby-boom generation was in their 30s and 40s, in the prime of their working lives, and I think it is fair to say that they have led the Japanese economy as both producers and consumers.

The baby-boom generation has now moved from being the supporter of the economy to being supported by it, and this will have a major impact on areas such as employment, medical care, and welfare, which is why it has been called the “2025 problem.

The 2025 problem aside, although the environment surrounding Japan is getting tougher, I am very uncomfortable with the pessimism and the “Japan is finished” tone spreading more than necessary in the media and social networking sites.

Many of the pessimism about Japan is often compared to Japan’s economic growth in the past. However, since the scale of the economy has shrunk significantly over the past few decades due to population decline and aging, I feel that there is a limit to the scale of economic growth that can be sought in the first place.

On the other hand, movements such as Sustainable Sustainability Society, SGDs (Sustainable Development Goals), and the shift to de-growth are spreading.

I personally believe that a shift away from economic growth is the key to Japan’s survival, given its scarce natural resources, low food self-sufficiency, and dwindling human resources.

While we do not completely reject the new capitalism that the current cabinet is pursuing, we cannot help but feel a sense of crisis when we see that the framework of this new capitalism is still based on the same model of growth and distribution.

I would like to study more in this field, as there may be some measures that can serve as a reference for Japan, such as in the Netherlands, which is trying a circular economy, and Sweden, which is promoting investment in human capital in Northern Europe.

日本は天然資源も乏しく、食料自給率も低く、また人的資源も先細りしていくなか、日本が生き残っていく道は、脱経済成長へのシフトが鍵だと信じています。循環型経済を試みるオランダや、人的資本への投資を進めるスウェーデンなど日本の参考になるモデルをもっと調べてみたいと思います。